Introduction

Imperial London: Women, Theatre, and Empire

Spring Break 2019

March 2019: An exhibition by Russell Haines in the Royal Chapel at the Tower of London displays the beauty of women’s diversity and power in faces overlain with verbal tags, one proclaiming “God is a woman.” The multi-paneled canvas stands adjacent to the altar beneath which, legend has it, lie the bodies of Jane Grey and Anne Boleyn, the latter re-buried there in an act of mercy and consideration for her noble lineage. Like many of the other experiences during this week, we stumbled fortuitously upon this celebration of women, the exhibit offering a juxtaposition both of women as agents and victims of power and as subjects and inspirers of the arts and the change art brings.

Elsewhere in the Tower, complementing the long-standing memorials to Sir Walter Raleigh, the lost princes, and the various exhibits of England’s military might through the ages are newer tributes to others directly affected by empire but previously left in the shadows of its annals:

Earlier in the week, we had visited Stratford-Upon-Avon to experience the origins of the man who staged monarchy for the Elizabethan age. Again fortuitously we had enjoyed a Royal Shakespeare Company production of The Taming of the Shrew, which flipped character genders thereby underscoring the prominence of women’s social roles. Even in Shakespeare’s all-male theatre world, the importance of women in public and private life meant that strong female characters were crucial to his plays. This 21st-century production captured that Shakespearean essence while featuring an entertaining contemporary production.

The immigrant experience central to our imperial theme synthesized during our foray to Brick Lane on a wet afternoon. Here we explored the markets and alleys that Nazneen wanders in Monica Ali’s novel of the same name and then enjoy a Bengali dinner amidst animated discussion of the many complicated issues everywhere evident. The industry, the artistry, and the consumption of the women, which keep Brick Lane and other mercantile areas of the city—the heart of empire and its post-condition—thriving are everywhere evident in this small stretch of London. So too are the vibrant arts. “The man who is tired of London,” quipped the saturnine Samuel Johnson, “is tired of life.” The woman too, he might have added. Women’s industry and energy is most remarkable here.

The theme I’ve been stressing here is fortuitousness: how well everything came together, seemingly miraculously. Yet, the maybe the strands we were looking for were there all along. Another factor in pulling all the threads together is the energy and enthusiasm of each member of this group. The curiosity and independence with which each pursued both the major themes of the course and their own archival research interests led to great conversation and discoveries. From corners of Stratford, to obscure nooks of London, to a hidden immigration museum, to conversations with Londoners, the students record their experiences here—and demonstrate why these courses are so successful.

I’d like to thank the College of Arts and Science, the English Department, and the Study Abroad Office for their generous help and making these programs possible.

TMC

Sarah’s Response:

I have always wanted to travel to England. Before she died, my maternal grandmother traced part of her lineage back to the Mayflower, and was always so proud of her English and Scotch-Irish heritage. She was an English teacher and made sure I grew up on Shakespeare, Austin, Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth, and so many others. 17 years ago I traveled to Ireland with my parents but still longed to travel to England. As I have never studied abroad, the opportunity to enroll in this course as the only Rhetoric/Composition student and venture to England was something I could not pass up. Even as a Rhet/Comp major, my background is definitely in Lit Studies.

I took the opportunity to travel to Canterbury Cathedral before our class “officially” started and that was one of the highlights of my trip. I was able to make mini- lecture videos inside of the Cathedral for my British Lit students at Campbell University, and I felt like I was stepping back in time. I have always had a fascination with Thomas Beckett, and since I am Episcopal myself I felt as though this was my own little pilgrimage.

Another true highlight of this trip was visiting Shakespeare’s Globe theatre, traveling to Stratford Upon Avon, and Anne Hathaway’s house and gardens. I found it fascinating the new Globe can only hold 1500 people, while the old Globe could hold 3000. This of course is partly due to capacity restrictions. I also never knew the Lord’s room/box was above the stage, but the explanation for this makes complete sense. It is also interesting to know that shows are not cancelled due to weather as it can add to a performance, and “the show must go on”. Our mascot for the trip, The Plague Rat, was picked up here. J

Traveling to Stratford Upon Avon was a dream. I wish we could have stayed more than one night. It was lovely to watch a gender bent performance of Taming of the Shrew put on by the Royal Shakespeare Company. As mentioned on the RSC website, “Shakespeare’s fierce, energetic comedy of gender and materialism [is turned] on its head to offer a fresh perspective on its portrayal of hierarchy and power”. The entire time we were watching this play, I kept thinking to myself, I wish more people in society could watch this version. Seeing it performed in role reversal, really helped solidify the absolute absurdness of the comedy. As we all know, Shakespeare was ahead of his time and surpassed all of his contemporaries.

Anne Hathaway’s house and gardens was incredibly insightful as well. There is so much I did not know about her life, as she always takes the back burner to Ol’ Shakespeare. I didn’t know her family lived there for 13 generations and that her grandfather was a life tenant who passed the tiny cottage down to his children, and then her brother bought it and renovated it for his own family. I was also a little sad to find out that there is no evidence that the ‘second best bed’ is the true “second best bed”, but after hundreds of years and everything passing through many hands, that is of course to be expected I suppose.

The National Portrait Gallery in London was wonderful. I have a huge love for the Tudors, so of course I had a hard time moving away from that section of the gallery. It was a lovely space that we were all able to enjoy together and being in that space, even for a short time seemed highly influential on a number of us.

Since I am currently researching warrior culture and the influence of war and community on individuals in military service, I had to visit the Imperial War Museum. This museum far exceeded my expectations and I was very pleased to have had the chance to visit and experience particularly the World War I exhibit.

Lastly, Brick Lane was truly a wonderful experience. Having read the novel, being able to explore the Lane and the surrounding areas really helped put everything into perspective. The food that night was the best on the entire trip.

There are so many others things to mention, The Tower of London of course, Sir Walter Raleigh, The boys in the Tower, so on and so forth, but honestly, I don’t think you want to read my rambles for another page. Love.

As this was my first and last time studying abroad, I am so pleased and blessed I was able to do so with this wonderful group of people. Xoxo. Sarah.

Bridgitte’s Response:

This post is cross-posted on the That Crafty Medievalist page as “That time I stepped out of time.” Or, “That time my wife left me for London for two weeks, and all she brought me was a mid-shelf bottle of Scotch.” Or, “That time I understood why Mom said, ‘Ok, so when and where is the next one?'” Or, “That time I looked at my bank after I got back and said, ‘Welp, I’m eating ramen for the next century.'”

I’ve been around the United States more times than I can remember – literally. I travelled across the US with my family every summer between 2001 and 2008, and sometimes fall, spring, and winter, too. I’ve been to most of the spaces in Georgia people are authorized to go, and some they aren’t, since we’ve been camping in it off and on for my entire actual life. I’ve been to Canada once (for a day, maybe) and seen Mexico across the Rio Grande.

But I’ve never had a passport, never had a stamp on a page, never seen anything outside my home continent, and only about a quarter of that, besides.

When Dr Caldwell advertised Imperial London: Women, Theatre, and Empire, I looked at my husband and begged him to let me go. It’s my last semester of coursework, I said, can we find a way to pay for it? And we could maybe afford one plane ticket, and we don’t eat out so much anymore so the food budget was fine, and since he’d been anyway and had to work, I went alone, which terrified me a bit, but I did it, and what a trip it was.

I considered, in this last week of wondering how do I sum up these epic two weeks in one post, writing about the costuming marvels I witnessed. Three shows – Taming of the Shrew, Waitress, Wicked – each brought something new to the table with their costumes and show designs, at least to me. I’ve seen Taming, though not gender-flipped and exquisitely Tudor as it was, but not the other two at all, so it could be that their choices are universal, and that when I [can afford to] see Wicked again, the dresses and styles and choices that visibly support the action and subtleties within the show will probably carry over across the pond; and it’s really hard to believe the “plaid grunge” and “fifties traditional waitress that shifts to modern after the plot turn” look of Waitress that really seems to be the heart of the show wouldn’t be here, too.

It’s hard to decide, without interviewing the costuming department, how much of the designs of each show were dictated in the script, or by directorial choice, or left up to the costumers themselves. With shows that travel/end up in different places like Wicked and Waitress, it’s hard to know. Taming‘s genderflip itself was on the director’s order, but I think, to an extent, he either worked with the costumers or “gave them their heads,” so to speak. From my time as a costume design student, we were encouraged to consider how the clothes we designed would reflect the concepts of the show, and I’m sure, if I’d gone into more, I’d have learned how to do what the RSC’s costumers had probably done – use the modified script as a basis for design and created sketches and defenses to run by the director, then bullied him into accepting them as they reflected exquisitely the characters he’d set up.

At the end of the day, though, all that is conjecture, which is why it’s so hard to dissect costuming from a live show. Your evidence is primary, and getting access to it – during or after a show – can be a tedious process at best. Too, your argument boils down to “the costumer” or “the director” made these decisions to use visuals to reinforce the subjects in the show, which also gets tedious, though the meaty bits don’t.

So instead of writing about costuming, I’ll write about liminal spaces.

An Old English class I’m auditing this semester focuses on landscape, how it impacts the works we read, and how, by analyzing and understanding the world around the author, we can better see and understand the works themselves. I’ve been reading about how Britain, specifically, has what many authors over the centuries have called simply “atmosphere.” They don’t really describe it, and have a hard time defining it, particularly because this “atmosphere” of the country is so hard to define and codify. Having been a closet naturalist and baby scientist for many years, I figured seeing this “atmosphere” for myself wouldn’t be too hard.

So I looked. I looked all over London. I looked in the grey daylight, so often spitting “rain” those first few days, and saw no “atmosphere” I could discern.

I looked in the streets, lined with cobblestone and wending in strange directions. I looked in the architecture, buildings close together, showing clearly their 400-year history butted up against “newer” buildings, those still 200 years young. I looked in the Globe, steeped in historical reconstruction, and in the galleries and museums all over the sprawling town.

I looked in the landscape of the countryside, where small fields, separated by hedgegrows and ditches and pollarded trees, stood green and verdant in the grey light, in the bright sun, in the subtle hues of dusk. I looked in those trees, some newly growing from cut branches, some reminding me of the old Whomping Willow in Chamber of Secrets with their spindly shoots growing from clubbed branches. I looked in the ponds and rivers in Stratford-upon-Avon, at the swans and ducks gliding gracefully and happily and protected in their homes.

But it wasn’t until I was on the plane home, looking over Ireland and the Atlantic ocean, that I realized what I’d been seeing it the whole time.

Liminal spaces, you see, are typically found in literature – Beowulf’s fens and marshes of Grendel’s home, or Midsummer Night’s Dream‘s gardens of Titania, or any space with no real sense of time, of the world at large, of “reality.”

This whole time, I’d been looking for that feeling of “atmosphere,” that inexplicable sense of place that is distinctly English. I’d been looking to see the fogs over the moor, or for Grendel’s ghost loping across the shadowy field, hoping to find it there or in the landscape somewhere, and when I didn’t feel it, I needed to shift my eyes, shift my focus somehow, slow down. But even when I did, it wasn’t there. Even when I stopped looking for it, I only felt other things, like the press of death and sadness and longing inside the Mummies of Egypt at the British Museum, like the wonder of sunrise in a new place.

No, it wasn’t until I was seated on my flight, “mile high tea” tidied away and lunch long over, having paused in reading my new Little History of Literature, during which I’d been laughing uproariously – it’s written by a cismale white Brit, after all – to visit the toilets. The lights were off when I went in, and had turned on before I came out.

That shift, small as it was, shocked me into understanding that I was no longer in that liminal space I had called England.

Come to find out, it’s hard to realize you’ve been in a liminal space until you’ve left one. At once it occurred to me that I was no longer in England, was no longer bound to the time differential that I had been while on land. I felt awake, myself again, not that I’d been asleep the entire trip, but that I’d been elsewhere. Folklore about going through faerie rings describe a similar phenomenon, and every time I read about it, I’d asked, How could you not know when you’d been elsewhere, elsewhen?

I felt so at home there, so adjusted, that I’d never even questioned whether I actually was somewhere else. It was a new place, yes, but similar enough to home and my other travels that I could – and did – adjust quickly. I loved it, loved being there and analyzing and remembering and documenting everything about it, and want to go back. Not right this moment, I’m too busy relishing being home, but sometime, yes.

How could I not know I’d been in that elsewhere space, that sidestepped land?

I’d stood not five feet from ravens long as my arm, creaky door noises coming from sharp, clacky beaks, the likes of which don’t begin to exist in Georgia. I’d pressed my hand to the glass protecting human remains that were perhaps millennia old and still looked, felt, emanated human. I’d adventured on my own, went to pubs and quiet spaces alike that I’d, back home, have shied from without a partner. I’d put my fear and worry and guilt aside and lived as I hadn’t for a long time, perhaps too much, now that I’ve balanced my checkbook (alright, I’m hamming that up just a bit). I’d stepped into a new PokemonGO community for mere moments, really, expecting nothing but a few folks to raid with and then be done, and came out the other side with friends long after I’d meant to be back in my room.

Maybe I’m new to world traveling, and this is a space – headspace? heartspace? liminal, yes, but beyond that? – that I won’t see again. Maybe I’ll see it when I travel anywhere again. Maybe it is a space that only England exists in. I hesitate to say that this experience was my version of this English atmosphere, as I don’t know for certain what any author’s before me really was, though it does seem to me no-one has used “liminal” and “atmosphere” together before. Maybe it happens to everyone. Maybe I only noticed it because of that opportune toilet visit. Maybe I only noticed it because I wanted to, because I was looking for this “atmosphere.” Maybe I willed the feeling into existence. Or, just maybe, we flew over a faerie ring in Ireland on the way in, and, on the way home, back out the other side.

Maria’s Response

Layer upon layer. Of dust, of grime, of ghosts. Representing waves of immigrants to London. In near-original condition, the Museum of Immigration and Diversity allows you to feel you are breathing the same air of the people who once inhabited the space. It’s a testament to the power of place. If the museum was a book, it would win a Pulitzer for its depth, its intrigue, its multi-layeredness. It’s no wonder Monica Ali has called 19 Princelet Street “London’s most important building.” In the city’s East End, a few short steps from the Brick Lane that Ali famously wrote of, this 1719 building “has migration written into its bricks and mortar,” says The New York Times’ Rachel Shabi. I couldn’t agree more.

I had the privilege of spending more than two hours at this museum, typically only open to groups by special appointment, due to its fragility. It was generously opened for me and another grad student from the University of Westminster by our amazing guide, Philip, who outlined the history of the 300-year-old building, and walked us through the “Suitcases and Sanctuary” exhibit created by local schoolchildren. Leave it to kids to figure out how to compellingly and poignantly communicate a subject as complex as immigration. Philip said he believes it’s the first museum in the world showcasing exhibits by nine- and ten-year-olds. And though many of these children, who created this exhibit fifteen years ago, are immigrants, they weren’t necessarily focusing on their family stories. “It’s all about empathy,” said Philip.

First, a little history: A family of French Huguenot silk weavers, escaping religious persecution, first lived in the house, followed by Irish immigrants, fleeing the potato famine, and Jewish immigrants, drawn to England for religious tolerance and a better economy, from Poland and Russia. In 1869, a synagogue (notably the only known one with a stained-glass roof) was built in the home’s garden space.

This layering of ethnicities, and intersection of stories, is striking, thanks to the innocence and creativity of the children from six local schools, who were instructed to act as “archi-tectives,” and think about what the building told them. The amazing result? They eloquently tell the story of not just the house, but the surrounding community, which was (and still is) home to a myriad of immigrants from all over the world – from India and Bangladesh to Jamaica and Eastern Europe. Open suitcases reveal rotting potatoes, stained handwritten letters, and mock newspapers. Videos (cunningly displayed in suitcases) reenact ship voyages, complete with tilting camera angles. Some displays are interactive; for example, visitors are asked to take a small luggage tag and answer this question: “You must leave your home in five minutes, never to return; what will you bring with you?” Philip wouldn’t let us peek at the mountain of already completed tags until we’d written ours. My answer turned out to be the same as my fellow student’s, and many others’: family photos.

Part of the home’s upstairs is now a gallery for Bosnian-born British artists Margareta Kern and Suzana Tamamovic, and Tibetan-born British artist Gonkar Gyatso. One of the most intriguing pieces, Gyatso’s Soft touch, is a Union Jack pillow, which from a distance, looks like a cozy place to perch. On closer inspection, it’s laden with nails – pointy edge up. Is Gyatso saying England seems welcoming from a distance for migrants – but not once you arrive?

“Brits are uneasy with the concept of immigration,” Philip commented, “unlike the U.S., which embraces it.” Say what?? I had to disagree. “But you have Ellis Island, and besides, more of you voted for Hillary.” Hmmm. I would have loved a more extended discussion with Philip, so I could have shared that since Trump took office, legal immigrants with specialized skills are being turned away at an unprecedented rate. But I digress.

After reluctantly leaving 19 Princelet Street, I headed to a nearby Turkish restaurant for a delectable multi-ethnic lunch of Greek salad and Turkish lentil soup. My Greek Cypriot mother, from the divided Greek/Turkish island of Cyprus, would have been proud. Then, ever so appropriately, I tubed to the Victoria Palace Theatre to see a play about how “a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman, dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot in the Caribbean by providence, impoverished, in squalor,” grew up “to be a hero and a scholar”? Yep, Hamilton. Another immigrant narrative. I sat next to a lovely woman wearing a hijab; we laughed and cried at the same times.

But that’s a story for another blog.

–Maria Mackas

Ahngeli’s Response:

As our journey continued to Stratford-upon-Avon, our Imperial London: Women, Theatre, and Empire class took us to the Royal Shakespeare Company’s The Taming of the Shrew, directed by Justin Audibert. The most significant part of this play was that it was a creative and inventive gender-flipped production of the Shakespeare’s play believed to have been written some time between 1590-92. Almost all the roles were therefore occupied by the opposite sex in this production as it played with conventions of the time of its origin and today.

This comedic play focuses on old traditions, gender, materialism, trickery, and the pursuit of true love. Audibert’s matriarchal reimagination of The Taming of the Shrew performatively attempts to deconstruct (our understanding of) heteropatriarchy, power, and agency. We find Baptista Minola, mother of two sons, trying to sell off and wed her oldest son Katherine in order for Bianco, her youngest and highly desired son, to be up for auction. Thus, the audience is confronted with a reversal of traditional power dynamics seen both in the roles of parents and children, as a mother is selling off her sons rather than a father his daughters. Considering that it is indeed a visual performance, this reversal was not only seen in the actors’ manners but also their attire. While the women were usually dressed in beautiful and pompous costumes, the men were dressed mostly inconspicuously.

This gender-flipped play makes the audience not only reevaluate the problematic dynamics between male and female in the original play but highlights that even in a matriarchy such imbalance cannot be fruitful. Furthermore, it extends the conversation to current gender and power based issues that society is struggling with as it showcases transgressive female dominance. Although the play is very much entertaining and thought-provokingly portrays women, the historically marginalized and disempowered gender, with abusive agency and actions, it does not represent any sort of equality but simply disenfranchises men. It can therefore not be seen as a utopian vision but rather as a way to cleverly highlight the named issues through change of perspective. However, one has to consider that The Taming of the Shrew is indeed a comedy after all. Although comedies often function as mirrors to society’s reality as they highlight its flaws and struggles, it is determined to provide a happy ending. So, in spite of all the characters’ (questionable) choices, imbalanced power dynamics, and abusive relationships, everything has to be resolved before the curtain falls.

–Ahngeli Shivam

Elisha’s Response:

The Women, Theater, and Empire study abroad course allowed me to cross the Atlantic and experience a European city for the first time. Although the focus of our group conversations typically stayed within the parameters of the course, what I learned extended beyond the scope of gender, theater, and literature (but I learned a lot about that as well!). Through the locations we visited, the people I spoke to, and my experiences with London, I was able to broaden my understanding of a culture intrinsically and historically connected to our own and continue to examine and navigate the construction of gender.

I came away from this trip with a much greater comprehension of Restoration-era culture, specifically in regards to theater. Reading The Rover in combination with seeing Covent Garden provided a unique scaffolding for understanding Dr. Caldwell’s descriptions of the Restoration drama scene. Obviously, the district has changed in the past 350 years (the vegetable market is now a covered shopping center), but the layout is almost the same as it was in the 17th century, and many of the buildings, including St. Paul’s Church, have survived, although with some renovations. Covent Gardens was London’s first piazza, a “modern” square that influenced the planning of many subsequent neighborhoods. Walking around the district, I had the sense that a weekend afternoon in Covent Gardens in the 17th century would feel similar; I saw street performers singing, acting, and doing magic and shops selling chocolate, coffee, and upscale clothing.

Getting a sense of the physical space gave me some context to Aphra Behn’s world. I can imagine that she took inspiration from the nighttime activities of Covent Garden when writing The Rover, especially considering Behn’s inclusion in John Wilmot’s social circle. Although she would not live to see it, Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies was published annually from 1757 to 1795 and contained descriptions of the district’s famous prostitutes. This perverse celebrity status reminded me of the way the male characters in The Rover speak of Angellica Bianca. Although an established entertainment and market district in the late 17th century, The Rover seems to anticipates the heights (or depths, if you’d rather) that pleasure culture in Covent Gardens would reach. I might be wide of the mark, but seeing Covent Garden as it is now helped me visualize it as it might have been: a vibrant, dirty, wonderful mixture of thespians, merchants, courtesans, and nobles.

Travelling to Stratford-Upon-Avon to see the Royal Shakespeare’s “gender-bent” production of The Taming of the Shrew proved an unexpected supplement to our reading and discussion about women’s role in British theater and culture. None of us realized that the RSC was going to swap the characters’ genders, and I was surprised when Lucentia and Trania, rather than Lucentio and Tranio, expressed their excitement at arriving in Padua. The gender-swap highlighted the play’s many absurdities: the gatekeeping of Baptista, the wooing of Bianca/Bianco, Petruchio/Petruchia’s “taming” of Katherine, and societal gender roles in general. Watching this production of The Taming of the Shrew reinforced my belief in the value of reexamining historical literature and drama from novel, modern angles. I found the scenes where Petruchia “tamed” Katherine (i.e., tortured and starved) to be of particular value. It immediately made me think of how I would feel if they depicted the scene with the original genders. Would I feel more disgusted? Or would/should this sort of treatment be equally reprehensible, regardless of gender? The new play was able to evoke these questions despite the reversal of the characters’ original genders. While our class did not come to a consensus on precisely what Shakespeare’s intentions were concerning his depictions of personal and societal violence against women, seeing the RSC’s rendition of “The Taming of the Shrew” added an element to the discussion that would not have been present otherwise.

One of my favorite things about London was how many historical places have been preserved, and this was nowhere more evident than at the Tower of London. Touring the Tower grounds was probably my favorite experience in London. The White Tower was constructed by William the Conqueror in the late 11th century (built near the 3rd century Roman London Wall, of which some sections remain!) and the outer wards were constructed over the next 200 years with considerable expansions made under Richard I, Henry III, and Edward I. The layout of the Tower has remained fundamentally unchanged since the late 13th century. Exploring a space with over 1,000 years of history enchanted me, and my interactions with the Yeoman Warders only heightened my fascination. I took one of their guided tours and learned all kinds of historical stories, from the beheading of Anne Boleyn to the escape of William Maxwell, 5th Earl of Nithsdale (during a visit from his wife, he dressed up as a woman, fooling the wardens!).

After the tour, I took some time to talk to my Yeoman Warder guide, “Bash.” He told me about his own military career and how he became interested in coming a Warder. Apparently, he visited the Tower with his son three years ago and was fascinated by the traditions of the Warders and the history of the Tower. I spoke to two other Warders, Lawrence and Gary, and they all gave me similar stories about how they first became interested in becoming Warders. Their appreciation of their culture’s traditions was evident in their tales, and I felt that their pride in upholding such a tradition was warranted. Lawrence, in particular, exhibited a scholar’s interest in the history of London. We spoke about the difficulties in discerning the truth of London’s history, as many documents were lost during the 1666 fire. Lawrence also admitted the bias of historical documents written by Englishmen. He believed in examining foreign historical documents in conjunction with British documents, stating that the truth of history probably lay somewhere in between them. Lawrence had a pseudo-transnational approach to his own country’s history, something I appreciate as an aspiring transnational literary critic.

During the tour, “Bash” mentioned that there were now two female Warders living at the Tower. I looked this up later and was surprised (although perhaps I shouldn’t have been) to find that Moira Cameron, the first ever female Warder, had been at the center of a highly controversial bullying case that led to the sacking of two of her male colleagues (although one was eventually allowed to return after issuing an apology). She was quoted in 2009, after the incident was resolved, as saying that she would never recommend other females to apply. However, in 2014, she became one of the faces of a recruiting campaign by the Warders. She said that “it was a case of breaking the mould and changing the place, rather than leaving and letting it continue. There was a small village mentality and I’m glad I stayed and got through it. It was four years and it was not easy, and I sacrificed a lot in that time” (I found this quote in numerous publications, but I couldn’t track down its source, so take it with a grain of salt). Her sacrifices were not in vain; Amanda Clark became the second female Yeoman Warder in 2017.

This whole series of events piqued my interest, so I did a lot of thinking about it after my time at the Tower. I think that they these bullying Warders are representative of a culture that we are trying to change; that sort of behavior has no place in the world we are trying to build. In a way, they echoed the gender expectations we found while reading The Taming of the Shrew, Brick Lane, and The Rover. I spoke to Lawrence, one of the Warders I met at the Tower, about diversity in the ranks of the Yeomen. Lawrence told me that he wasn’t around when Moira Cameron went through her ordeal, but he told me that he was a first himself. Lawrence Watts became the first black Yeoman Warder in 2016. I found this surprising; a female had become a Warder before a person of color! He laughed at my surprise (Lawrence had an easy smile that was very endearing). He said that diversity of any kind took a while to reach the Warders; since you have to have 22 years of military service to be eligible, those gaining acceptance now had to have joined the military in the 90’s. He also told me that he had gotten a fair amount of teasing, but that it had been almost entirely good hearted. He believed that if you did right and showed your real worth, your colleagues would accept you. He said that he saw the truth of this in Moira’s experience.

I think that my conversation with Lawrence was an illustrative example of the theme of women as objects and subjects of the British Empire. He received almost no serious bullying (according to him, at least), and I believe that because Lawrence was a man it was easier for a still almost entirely male institution to accept the kind diversity that he represented. However, Lawrence himself seemed very accepting and proud of the diversity, of both gender and race, which is beginning to bloom in the Yeoman Warders’ ranks. I see a parallel between Aphra Behn and Moira Cameron; they were both women trying to excel in a predominantly male institution. They were both treated as objects of the British Empire; Moira Cameron became a marketing symbol for one of London’s oldest institutions, and Aphra Behn is a historical female symbol of Restoration era drama and literature. However, they both also acted as subjects, finding agency in their female identities.

I believe the issue which Moira Cameron, Aphra Behn, and all women in history and today have to deal with is an internalized and always already present male exceptionalism. I find it interesting, however, that in order to identify as male, we must have a female other. Throughout our journey, I developed a better sense for how British culture depended on this female other to define many of their institutions and cultural identities. As the only male in an all-female group, I noted how I constructed my own masculinity by its difference from what I perceived as feminine. I’ve been aware of this for a few years now, but this trip really reinforced this concept for me. I’m grateful for the opportunity to experience London, but I’m especially glad that I was able to see it through the lenses of gender and theater. I don’t know if I (or our society/culture, for that matter) will ever be able to completely overcome some of these gender constructions which I have learned and internalized over the course of my life. However, I believe an ongoing attempt to continue deconstructing such identities is valuable, regardless of how often I fall short of the project. Reading texts such as The Rover, Brick Lane, and The Taming of the Shrew and talking about them in an environment like this study abroad course are an important part of this project.

Rachel’s Response:

This was my first time visiting the United Kingdom, and my initial response to London is mostly for its mere aesthetics as a result of empire. The collection of aesthetics and objects from all corners of the world, many of which we had the pleasure to see during our time there, herald the vast city as a corridor between east and west, while a layer of twenty-first century advertisements upon nineteenth-century building façades blurs lines between then and now. Makes me think of how our modern, globalized world is but a tablecloth over centuries of imperialism. What manifests now simultaneously forces me to recoil and draw nearer in utter fascination. Shabana said it best: a “colonial hangover.” What I have observed both in London and in our readings for the course affirms an overwhelming connection between English imperialism and our capitalist modernity. The question that The Rover, and maybe even The Town Before You, though the approach is completely different, attempt to answer is what happens when empire begins to collapse in on itself because of capitalism/wealth? And because of ambition? In the eighteenth and nineteenth century, it seems that people, namely women, become expendable: a past from which we have thankfully escaped—or have we?

“For some, hostility is an everyday experience…” That was one of the many quotes inscribed on Russell Haines’ mixed media collage entitled “Faith, Hope and Charity @ the Tower” at the Chapel Royal. This message also appears most central to Waitress and The Taming of the Shrew, both plays about two very particular kinds of women. The multimedia piece by Haines is a celebration of immigration, multiculturalism, and femaleness. Haines also made a mixed media collage of male portraits; the pair are mirror images of sorts. In light of Brexit and other nationalist movements around the world, immigrants continue to play the role of scapegoat for problems initiated by the very powers who choose to do the scapegoating. Centuries of colonization and improper trade deals scarred the world, desecrating economic systems through subjugation and pillaging. It was pretty surreal to stand at the capital (London is one of them, at least) of it all. When the slave trade ended, and the imperial era gradually phased out into modernity at long last, immigrants could exert some sort of economic, geographic and social mobility, but where does this leave immigrant women? I think Haines must have been thinking about this too…

The memorial landscape in both American cities and London, like all landscapes, is indicative of what social movements and political regimes shaped the region. A caste system of race spread with triangle trade routes, subsequently disseminating to the United States and manifesting in the continuation of white supremacist attitudes to this day, while European society appears to be decades ahead in progress. I do not see public monuments to the Cromwellian dictatorship in the UK, yet when I return home, I observe numerous Confederate monuments that dot the landscape in the south. What would I feel if I were a person of color, here, in Atlanta? I look at the street names, the names of businesses, restaurants, tube stations in London; many of these names are monarchical and, consequently, imperial. “King’s Cross”, the “Victoria” line, “Queen’s Park Hotel”, these are just a few examples. Ideologically speaking, naming came from those in power to serve as a reinforcement of the monarchical system. I wonder what social partitioning results from something as arbitrary as naming… and I wonder, where do women fit into this imperial narrative? Well, as we talked about in one of our discussions in Paddington, the colonial model does not work without women. The colonization of women’s bodies via reproduction is necessary, first, in order to colonize new territory, and not only of the colonists, but the colonized women as well. I plan to explore ways in which writers like Behn took back the commodification of the female body to turn a profit in her imperial world in my term paper for the course.

–Rachel Adornato

Ivey’s Response:

London is a city I’ve visited many times; it is a city where I feel at home, where I have certain routines. Though I have been to London before, it has been a long time since I’ve spent more than 36 hours there at once. It has been a long time since I’ve attended plays, visited cultural sites, or come to London while studying anything.

Coming into our trip to London I will admit I felt a bit stuck on exactly what direction I hoped my research would take. I feel many people had theirs exactly nailed down but all I had were several links, a few common threads from the texts that excited me. I come from a background of interdisciplinary study, particularly where the study of studio art and poetry meet, so I already knew I was very interested in the way that art can often times transcend genre. I was also keenly interested in the ways that texts, plays, comics, or even paintings can both serve as a means of transmitting information to the public, and how easily the power of that art can be used as propaganda, or at the very least how easily different forms of art can be used to dissimilate ideas that are unflattering or unkind, and perpetuate stereotypes. Similarly, I found myself fascinated by ideas of gender and social status, and who was the intended reader/viewer of such, whether it was a play, a painting, or even historically what space one was allowed to occupy within the places where art is experienced.

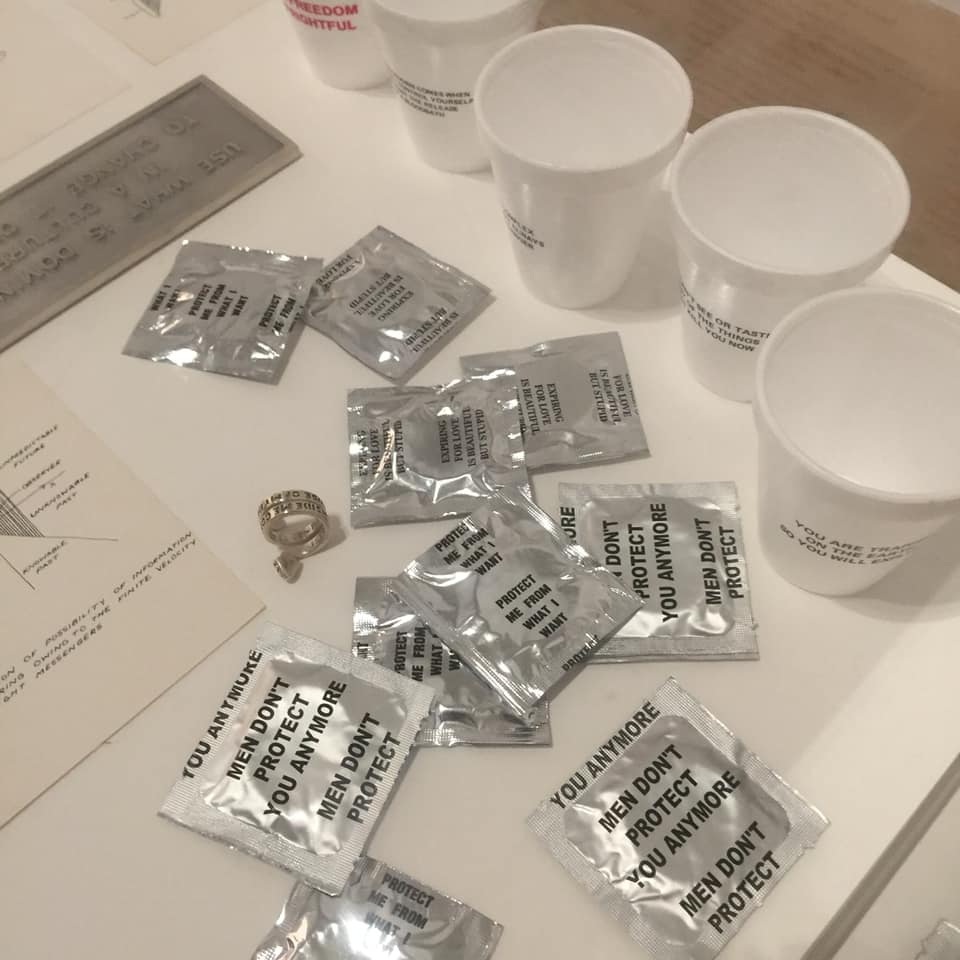

In a trip full of many poignant moments, there were three main experiences that I felt most informed my paper and my research during the study abroad trip. The first experience I truly felt privileged to stumble occurred at the Tate Modern, where I sawn the fantastic exhibit that they currently have up with many pieces by Jenny Holzer up. Jenny Holzer is an American artist and a neo-conceptualist, she uses multi-media to focus on the delivery of words and ideas in public spaces, which actually tied together my MANY interests within the course together quite well! I was a bit blown away by the kismet of it all. I was familiar with her work before the course, but I was really taken by this exhibit. I even cried. The first room was filled with lines and lines of statements- many of which seem innocent at first, but upon further inspection (and particularly within the context of other statements) are more likely meant to be inflammatory. Some of the statements are more obviously incendiary, and many are so poignant that they inspire sorrow or deep internal reflection. As a mother, many of her statements on motherhood and how we raise girls and what we teach them hit especially close to home. Women are meant to be constant chameleons, changing to shift the attitudes and ideals of the men around them. We are objects for consumption, meant to be molded into whatever will please men the most. Madonna or whore, fragile flower or snarling lioness, women must always fit into the role that men have assigned for them. This exhibit aligned with so much of what I was already interested in, and I thought tied in well with many of the texts. I went back to the Tate again for more individual research.

The gender-bent Taming of the Shrew was obviously fabulous and WOW just so rich! The dialog and discourse we had the next morning was also the best that I felt we had the whole trip. The Taming of the Shrew is admittedly not one of my favorite Shakespeare plays at all, and while I was still excited to see one of his plays performed at his birthplace, I felt slightly disappointed that play would be the one I would get to see. Then we actually got to the play, and though it took about five minutes of confusion I realized the genders were subverted and I was instantly fascinated! It can be triggering to watch a straight typical reading of the play (though it remains a fascinating example of how far we’ve come, and what we stand to lose if the modern political climate continues on this path…) the play in Stratford was comedic. The way Kate is broken down mentally, physically, and emotionally is rendered humorous in the gender-bent version, but even it still falls prey to some gender stereotypes. Petruchia often comes across as shrill and hysterical. She is a gold digger, just looking for a rich husband and some mad sport in the process. The gender-bent version does treat women more kindly than the traditional reading, but even it is not immune to gender stereotypes.

The final experience that really felt relevant to the ideas of gender, and how women are often treated (mistreated) was this common theme of MANSPLAINING that I felt like we were constantly subjected to, that I believe Anna also touched on in her blog post. The first night at dinner, the waiter was very condescending and would not allow Maria, Rachel, and Anna to split the appetizers we had chosen, as we were not that hungry. He would not hear our arguments that what we had chosen to split tapas-style was around the same price as if we had each ordered an entrée. The next day, at a convenience store the clerk was very rude as well. And don’t even get me started on the train operators! Interestingly enough, the best interaction we had with a man who explained anything to us at all was actually at the Tate when a kind museum worker walked us through ordering a fine art print. He actually took the time and listened to what we were asking instead of assuming we had no knowledge whatsoever of ordering a print. Amazingly, during this interaction we felt seen and heard as humans. How wonderful it was to have a conversation with a man who we did not feel spoke down to us. It is also interesting to me that this occurred within the sacred sphere of the “art” world. In a modern museum, are women finally getting the “space” that they need to be seen, heard, and treated as equals? As beings with a brain capable of intelligent thought?

After gathering so many rich threads on my trip to London, I look forward to further research and the process that will be weaving my thoughts into my final paper! I feel grateful for the opportunity to have been so inspired by what I was seeing, reading, and studying, but also for the dialog I had with my fellow scholar travelers along the way.

Anna’s Response:

When I read the advertisement for the Spring Break class on Imperial London: Women, Theatre, and Empire, I knew I had to go; it was a culmination of four of my most ardent interests. The reading list was similar to a list of my favorite books and plays: Brick Lane, The Goblin Market, Swing Time. I signed on immediately.

A few months later, arriving in London several hours later than planned, due to flight delays back in the states, I had to hurry to the hotel to meet the group. Having been to London a handful of times before, the process from Heathrow to the Tube to the hotel was fairly smooth and familiar, though I did spend several minutes looking for the hotel on the wrong side of the road. Once in London, things kicked off quickly. We headed to Covent Garden for a late lunch (hello, hand pies!) and browsing in the old-theatre-district-turned-bougie-shopping-destination. There are, of course, still many impressive theatres in Covent Garden and the surrounding area.

Later, at dinner, we ran into our first of many condescending mansplainers, who seemed to believe that our group neither understood how restaurants worked nor how to order food. This scenario would be repeated in many variations to the women in our group over the course of the week. At first, I was baffled because it was happening so often and so blatantly when I had never before ran into that kind of behavior on trips abroad, but I eventually was led to decide that the cause was that we were a large group of almost entirely female travelers. In any case, the experience(s) served as a mirror for the literature and dramas we were reading and watching about the role of women and how we are seen/treated/molded. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

And yet, in Stratford-upon-Avon, home of William Shakespeare, who we (as a culture) generally accept as both our greatest poet and our greatest playwright, history lurked around every corner, in the original stone floors of Shakespeare’s birthplace, the twisting, small streets, the slow-moving river with its barges, and still the future is here in the brilliant, genderbent production of The Taming of the Shrew that we watched at the Royal Shakespeare Company.

Oddly, for someone who is usually opposed to the sexist and frustrating storyline of this particular play, I have now seen two productions of it and both have been cutting-edge, thrilling, and gorgeous experiences. This time, the gender-swapped roles of the “shrew” and the suitor, as well as of our Bianca/Bianco, the ideal woman made into a man, and Hortensio, and even of the mothers who are selling off their sons rather than fathers selling off their daughters served to highlight and make a mockery of the absurdity of the play and its morals. When it is a man being deprived of food and water, kept from sleeping, and otherwise psychologically tormented, we are suddenly unable to justify the behavior the way generations of audiences have justified Petruchio’s behavior towards the female Katherine and even supported it (after all, one doesn’t find something funny unless one is in on the joke). While the original version of Taming is clearly aimed at a presumed-male audience and used to perpetuate discrimination by making it comical, this version turned that on its head and, in doing so, showed how we can redeem old art in a new age by such creative and thoughtful tactics.

Back in London, we saw Waitress, a modern musical with clearly progressive themes of sexual liberation, motherhood, and women making their own futures. I loved the film version years ago so I wasn’t surprised that I loved the musical as well. I will admit that, as a childless person, I tend to get prickly at the theme of “my life started to matter when I became a mother” because it often indicates that women who aren’t mothers are less valuable. Like, would you not leave an abusive marriage purely for yourself? No? Still, I think the storyline worked for this show and I enjoyed it immensely.

Skipping ahead, a couple of us also saw Wicked a couple of nights later on our own and I was struck by the themes of imperialism and womanhood/personhood that resonated with our course focus and with current political climates.

On Thursday, our archival research day, I spent a large amount of time at the V&A, specifically in the Theatre and Performance exhibit (which I had never seen before despite this being my fourth visit to the museum, perhaps because it is really difficult to get to) and took a lot of notes. I tend to be the person who reads every single plaque in an exhibit, which can annoy whomever I’m there with but provides me with many a useful fact or crumb for writing and research. The costumes they had on display were mesmerizing as well.

In addition to the plays, we also toured the Globe theatre–I’ve been to a couple of shows there but have never had the guided tour and found it really interesting. The idea of shared light (in which the actors can also see the audience) hadn’t occurred to me before, though I suppose it should have. We then dashed over to the Tate Modern for a quick visit before our train to Stratford-upon-Avon (yes, I’m jumping around in time here) and OH BOY. There was a phenomenal exhibit by the American neo-conceptual artist Jenny Holzer, in which she highlighted feminism and female struggles using words. And poems! I took photos of basically every plaque in the exhibit to use in my paper. Honestly, I’d try to describe it in further detail, but I worry that it would just be a jumble of exclamation marks and curse words. I’ll attach one of the photos I took here:

As the week progressed, my idea for my paper solidified. I’d gone into the course knowing I wanted to write about something connecting poetics with theatre with feminism, but not sure exactly what. I’m fascinated with the idea of using words and visual as presentation/performance and how that language and presentation changes reception. I’m thinking out loud (in writing?) here.

Other highlights included a tour of the Tower of London in which a very amusing tour guide/beefeater used the occasion to point out hypocrisy in political policy among other things. I hadn’t expected that and, despite his digs at millenials which are always a cue for an eye roll from me (like, yeah we’re on our phones a lot but you guys destroyed the economy and the education system), I loved it. Of course, one can’t visit the Tower without thinking of a few famous women who met unfortunate ends at the hands of the patriarchy. A monument is set up to memorialize the beheaded, but I found myself agreeing with the beefeater that it looked like a modern coffee table had been plopped down at random. I wish I had taken a photo purely to illustrate how true that comparison is.

Speaking of beheaded women, we also visited Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum and, though I initially was not at all excited by the prospect, it turns out that taking selfies with Mary, Queen of Scots is something I am really into.

After visiting the wax museum, we discussed, in tandem with a discussion about the National Portrait Gallery which I didn’t visit on this trip but had previously, the clear ranking systems of both museums (royalty first, then doctors/scientists/other valued professions, then regular folks) and the inclusion/seclusion of who was there and who wasn’t. (I’ll use this moment to bitterly mention that Donald Trump was included in the wax museum–ugh.) Obviously, seclusion isn’t new in any of its forms and has deep ties to the focus of this class. Remember when theatre rules went so far as to forbid women from playing women on stage? (Women also couldn’t play men on stage. Or children. Or animals. Women couldn’t be actors is what I’m saying). Seclusion has often targeted women, people of color, immigrants, the less wealthy, etc. Inclusion has (still) been extended only to the select few exceptions in those categories.

I found this course enlightening in the way it allowed me to experience and think about things I already knew in a place I was already familiar with while also providing new materials and experiences and allowing me the space to cultivate my ideas on things like, hey, I’m a woman and I want to not be mansplained to by the guy I’m buying a bottle of water from. (Okay, yeah, I’m still annoyed by the condescension. At least it provided some primary research though.)

I didn’t mention our visit to Brick Lane here, but the novel is one of my favorites. I went on a walking tour of the East End/Brick Lane a few years ago which was really valuable to my read and re-read of the novel. This time, I spent much of my day in a vintage warehouse in the East End and then having a delicious korma curry dinner (and foregoing the naan–curse you, gluten intolerance) with the group. While I am still suffering from jet lag and exhaustion because I went to Ireland for the weekend after the course and then flew straight to Portland for a conference (whyyyyyyy), I’m looking forward to getting to articulate my research and ideas in a more tangible and thorough way over the next few weeks.

Anastasia’s Response:

I signed up for the Imperial London: Women, Theatre, and Empire course because I needed to fulfill a course requirement, and I could think of no better way to do so than with a week-long trip across the Atlantic. As a literature student, I’ve had the pleasure of reading many British novels, poems, and plays, but this was the first time I would experience the place and the culture I studied. The trip itinerary only made me more excited and eager for the trip. I was most excited about seeing plays while in London. In my imagination, Britain somehow seemed like the birth place of plays, even though I know that’s not true. Maybe it’s because Shakespeare still sits on top of the cannon as a playwright and a poet. I was also looking forward to being on Brick Lane and seeing the culture Monica Ali writes about in her novel of the same name. Though the trip meant I wouldn’t really have a restful spring break, I was ready for the trip to London.

Visiting Stratford-Upon-Avon was one of the highlights of this trip. Not only did we visit Shakespeare’s birthplace, we also attended a Taming of the Shrew (Taming) at The Royal Shakespeare Company. I admit that Taming is not my favorite Shakespeare play, but RSC gender flipped portrayal of the play was a welcome surprise that left me stunned. For a class focusing on women and theatre, the shock of watching a male dominated play switch to a female dominated play was a welcome experience. That is not to say that the play is still deeply problematic even when gender flipped. Watching women objectify and commodify the men only highlights the ridiculousness of the play’s original premise. However, the actresses brought the play to life and made the flip believable and very enjoyable. While the play was the highlight of our visit to Stratford-upon-Avon, I also enjoyed visiting Shakespeare’s birthplace. Though the house was crowded with visitors, it still felt scared. Maybe that’s because we have romanticized everything to do with Shakespeare, but it was truly an honor to be in his first home. When we returned to London, I had more than my fair share of souvenirs to commemorate the visit.

The trip to Brick Lane preceded our trip to Stratford-upon-Avon. Though Brick Lane has changed the from the time Ali describes in her novel much of it remains the same. People still live above and around the many shops and Bangladeshi restaurants that line Brick Lane. I enjoyed walking through the markets towards the back of Brick Lane. The stalls were filled with food, clothing, and jewelry. It was a busy strip, but it felt comfortable. That night we ate at a Bangladeshi restaurant and I couldn’t help but wonder how Nazneen would feel about the changes made to Brick Lane, if she were a real person.

Apart from our scheduled trip and visits, I was able to see Buckingham Palace, Big Ben, and the London Eye. Walking along the Thames looking at Big Ben and then gazing across to the London Eye was a tranquil experience, even in the bustle of tourists. I could only see the face of Big Ben, as it was in the process of restoration, but it was still beautiful. The history and the aesthetics of Big Ben and the Thames was palpable and made the experience breath taking. And even though I am not a fan of heights, I appreciated the London Eye simply because of its majesty as it stood on the river. After we had our fill of the Thames, we made our way over to Buckingham Palace. Honestly, the Palace seemed much smaller in person. Watching the guards march back and forth was entertaining, but the most beautiful part of the Palace was the fountain right out front. The statues adorning the giant fountain were beautiful. A woman donned armor and was surrounded by children, seeing her reminded me that this trip was about the women who were just as responsible for the life and culture just as much as the men where.

Even though the trip to London was an amazing experience, I wanted to see more. Specifically, I wanted to see Black London. I saw people of color and Black people in and out of the travelers on the subway, but I wanted to see their culture. When we went to the National Portrait Gallery, most of the face on the wall were white. It almost seemed as if Black and Brown people contributed little to the making of London and its culture. It made me curious to see how Black Londoners saw themselves and what their parts were in creating that beautiful city.

One of my favorite parts of traveling through London was the accessibility of the subway. When we first began our trip, two other classmates and I struggled to by tickets for the train to get to Paddington Station. A train worker took pity on us and spent thirty minutes helping each of us buy tickets and encouraged us to get a week long Oyster pass that would allow us access to Zones One and Two for the entire week. To our surprise he was our train driver. As we reached our stop he made a special announcement to let us know and wished us luck on the rest of our journey. I was pleased and it started a week long love affair with the subway. I loved hopping from platform to platform to make it switch and catch the trains. It made the trip so enjoyable and easy to navigate. I think I would have missed something if we had to take Ubers and taxis. Riding the subway made me feel like I was apart of the city and apart of the culture, even if only for a week. Even now I still smile when I remember the constant reminders to “mind the gap between the train and the platform.”

—Anastasia Latson

Dionne’s Response:

I posed a query to my literature professor about the term subjectivity, hoping for clarity on a word that is heavily used in academia but lacks clarity and context in its employment. “What is subjectivity,” I asked. He answered by writing a simple sentence on the board: “The cat ate the bird.” He asked me to identify the role of each word in the sentence, and employ my knowledge of grammar and its usage (thank goodness for grammar class). I quickly referenced the subject (the cat) and the predicate (ate the bird) of the sentence, and identified the articles. He immediately followed by asking me which noun was completing the action (had the most agency and power in the sentence), and which noun was being acted upon (had the least agency and power in the sentence construction). I replied that the cat, of course was the subject of the sentence; the bird was the direct object. What followed was a discussion on grammar, subject and object, agency and power, and construction. Through the example, my professor, explained how an examination of this sentence gives us an idea of how subjectivity and objectivity functions in cultural production. The cat (the subject) is the primary actor of the sentence. The subject is primary in construction and essential to understanding the meaning/message. The message is complete with the subject completing the action. The subject, however, acts upon the direct object; the object is given little meaning, authority, power or agency. The object is simply present to add meaning and color the subject. My professor’s example stuck with me, and I began to look at subjectivity through that lens in cultural narratives – through memory in museums and literature.

My study abroad to London was my first visit to Britain. I knew the national, colonial, and cultural history of the city very well, and expected to see the manifestation of these narratives and realities in the cultural material produced. With subjectivity and objectivity fresh on my mind, I paid attention to the cultivation of the national narratives and how the colonial project and the role of women showed up in the culture of London. My first interaction with the national narrative was the National Portrait Gallery in London. The aim of the gallery is “to promote through the medium of portraits the appreciation and understanding of the men and women who have made and are making British history and culture, and … to promote the appreciation and understanding of portraiture in all media” (National Portrait Gallery). As I perused the beautiful gallery and permanent collections on the history and culture of London, I noticed that I did see the colonized; I only saw the colonizer. Through a winding maze of portraits capturing the face of London, I only saw two faces of color – African, male, one Muslim, and one kneeling to honor and accept Christianity (a Western religion) as a saving grace and gift from the colonizer. The subject and object construct played out right before me as I recognized the lack of the African presence in the portrait gallery. The colonized were the objects of the national message – existing on the periphery, with little agency, power, and primary stories to be named and recognized as a part of the national narrative. The cultural material, as used as a form of collective memory making, did not reflect the symbiotic relationship of race and the rise of the colonial empire of England.

This outward expression of the national narrative as seen in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery gave me considerable pause, but pushed me to find the voices and narratives of the colonized. During the latter portion of my visit, I visited the reading rooms of the British Library. Browsing their collection of African writers and authors felt like rummaging through a cultural treasure chest of voices, realities, and histories that were overlooked. While I considered the mission and goal of the portrait gallery, I still felt very weary by the lack of images and portraits of those who built the Western empire through their captured and enslaved bodies and the ravaging of their homelands. As I held an early copy of The Narrative of Olaudah Equiano, I questioned why his portrait didn’t adorn the walls of the gallery. Mary Prince’s account of slavery and her willingness to be a voice for the captive (the first female voice) didn’t merit her portrait on the walls either. Though this lesson seemed a significantly difficult one to bear, I left with a sense of hope that the work I do could extend into the public domains and shape the national narrative. As a student of literature and culture, I can use my experience to remove the “othered” voice and presence from the margins and into the light of subjectivity.

Shabana’s Response:

Born in a colonized country like India, grown up in a thoroughly British-influenced society, people of my country are groomed and influenced to the core by the British culture. The Study Abroad class in London was specifically helpful for me because it gave me an opportunity to explore the unknown I heard about all my life, the unknown that surrounds and rules the lives in a colonized country, which although has freed herself from the colonial rule long ago, is still present in the spell of that colonial hangover that perhaps will never vanish.

As a five-year-old girl, I listened to never-ending stories about how the colonialism took place in India, what were the consequences, how it stopped, and what were the repercussions even long after the British colonial rule ended. Ever since, I had a tremendous penchant to visit London to explore with my own eyes everything: from the descendants of the rulers to architecture to fashion to language and to everything else that we sometimes cannot even imagine. Along with India, Bangladesh and Pakistan, the two modern-day independent countries, were under the colonial rule as well. Some Bangladeshi people actively moved to London after the colonialism was over and established a predominantly Bangladeshi culture in Brick Lane, London. This place was of some extra importance to me for a couple of reasons: first, I wanted to discover and explore a place in London that is even though predominantly Bengali, has both Bengali and English perspectives. Brick Lane is filled with Bengali letters written all over the place, Bengali foods, clothes, and Bengali grocery stores, but ultimately lacks the independence that it had fought tremendously. The novel, Brick Lane, by Monica Ali demonstrates the internal conflict and paradox of the protagonist woman, who came to London and currently trying to shrug off her Bengali identity but is caught between the eternal crisis of her two identities. Roaming around Brick Lane, Holding Monica Ali’s Brick Lane in Brick Lane, I surrealistically felt like Nazneen would come out through one of those cramped doors, wearing a long coat over her red saree, trying to conceal her Bengladeshi look, loosening up her bun, speaking to a stranger with a British accent, and dreaming about wearing short skirts and other “western” clothes that will potentially allow her get rid of her burdened identity.

The question of identity became even more prominent when I visited Imperial War Museum, London. My special attention regarding my research was on the 5th floor of the huge building, where the Holocaust exhibition was displayed. Encountering the tremendous psychological and physical violence in front of my eyes was the most astounding eye-opener for a person like me whose research intersects between violence in the Holocaust and colonialism and caste violence in India. The pictures, pieces of writings, and the banners are at times breath-taking and disorienting. Knowing the dark past in the whole trip of the world is a phenomenon that I will cherish forever. These demonstrations correlate with my research on Indian caste hierarchy and system of violence by the superior to the inferior.

Along the lines of supremacy and inferiority, another ambition was to explore the one of the most famous attractions of the whole trip, Stratford-upon-Avon. Not only because it is Shakespeare’s birth place, but also because the place holds so much of history and culture and convention, I was more attracted to this place than any other.

It is sort of an unbelievable thing for a small-town person from India to encounter the place where Shakespeare must have roamed and written. The imperial connection in the small town although was lost, I could almost hear the voice of the literary shelter I had been so eager to hear ever since I started studying literature back in India. The Shakespeare I studied in India and the actual comprehensive Shakespeare in Stratford were different; however, they somewhere (honestly, I do not know what that thread is) mingle in a small thread. And I guess that thread is keeping all of us, the literature people, enthusiastic about more research on Shakespeare both in India and in London.